Late-Stage Relational Disengagement (updated)

In some relationships, disengagement appears sudden from the outside but follows a long period of accumulated strain. Communication stops, emotional availability collapses, and contact may end entirely. To observers, this can look abrupt or disproportionate. To the person disengaging, it often feels overdue.

This article describes that pattern as late-stage relational disengagement: a decisive withdrawal that occurs after repeated failed attempts to repair, tolerate, or adapt to an ongoing relational stressor. The term is descriptive rather than clinical. It names a commonly reported experience without claiming diagnostic status or universal validity.

Sidebar: “INFJ Door Slam” — Where the Term Comes From

Some readers may already recognize the pattern described in this article under a different name: the “INFJ door slam.”

The phrase comes from communities discussing the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), a popular but non-clinical personality framework that categorizes people into sixteen types based on four preference dimensions: where people focus their energy (Introversion / Extraversion), how they take in information (Intuition / Sensing), how they make decisions (Feeling / Thinking), and how they orient toward structure and closure (Judging / Perceiving).

One of those sixteen types is INFJ, which stands for Introverted, Intuitive, Feeling, Judging. In MBTI literature and popular descriptions, INFJs are often described as inwardly focused, highly attuned to patterns and meaning, sensitive to emotional and interpersonal dynamics, and inclined toward structure and resolution.

Within MBTI-oriented communities, the term “door slam” is commonly used to describe a moment when someone identified as INFJ abruptly disengages from a relationship after prolonged, unresolved strain. The behavior is often described as sudden from the outside, but experienced internally as the final step in a long process of tolerance, emotional exhaustion, and failed repair attempts.

This article treats “INFJ door slam” as a cultural reference point, not as a scientific explanation. The underlying pattern — withdrawal following cumulative relational strain — is not unique to any personality type, nor does identifying with INFJ imply that someone will behave this way. The usefulness of the term lies mainly in its attempt to name a pattern people recognize, even though the framework it comes from is informal and non-diagnostic.

What the Pattern Describes

In practice, late-stage relational disengagement tends to involve:

- sustained emotional investment over time

- repeated attempts to resolve or tolerate relational strain

- gradual internal withdrawal that may not be visible externally

- a final, decisive reduction or cessation of contact

A key feature of this pattern is that the visible break often occurs after the emotional decision has already been made internally. What appears sudden is usually the last step in a long, private process.

How It Typically Develops

-

Tolerance and repair attempts

Individuals experiencing this pattern commonly report giving many chances, revisiting the same conflicts, and attempting to adjust their expectations or boundaries in order to preserve the relationship.

-

Emotional exhaustion

When core needs, boundaries, or values are repeatedly ignored or violated, continued engagement becomes psychologically costly. Over time, this produces fatigue rather than anger, and persistence begins to feel unsustainable.

-

Internal disengagement

Before any external cutoff occurs, emotional investment often declines internally. The relationship may still exist in form, but not in felt connection. At this stage, the individual is often no longer seeking repair.

-

Final withdrawal

The final phase involves a clear behavioral shift: reduced communication, emotional distance, or complete disengagement. This step functions less as punishment and more as self-preservation.

How It Is Often Misread

From the outside, late-stage disengagement is frequently interpreted as impulsive, avoidant, or excessively harsh. This misreading is common because the earlier phases—tolerance, fatigue, and internal withdrawal—are often subtle or invisible. Social psychology research on attribution bias shows that observers tend to overemphasize personal traits while underweighting situational factors when interpreting others’ behavior (American Psychological Association: Fundamental Attribution Error).

Disagreements about this pattern tend to center on timing rather than intent: observers focus on the suddenness of the exit, while the disengaging individual experiences it as the end of a long process.

Relationship to Established Psychology

Late-stage relational disengagement is not a formal psychological diagnosis. However, it overlaps conceptually with well-documented phenomena such as emotional withdrawal under chronic stress, erosion of trust, and responses to repeated unmet expectations in close relationships and work environments, including what organizational psychology describes as breaches of the psychological contract (Rousseau, 1989).

These overlaps suggest that the pattern reflects an interaction between individual limits and contextual pressures rather than a fixed personality trait.

My Own Experience

When I first read about “the INFJ door slam”, I immediately recognized the pattern in myself. For what it’s worth, I have taken abbreviated personality assessments and always tested as INFJ or INFT. More importantly, independent of typology, I strongly recognize the pattern described here.

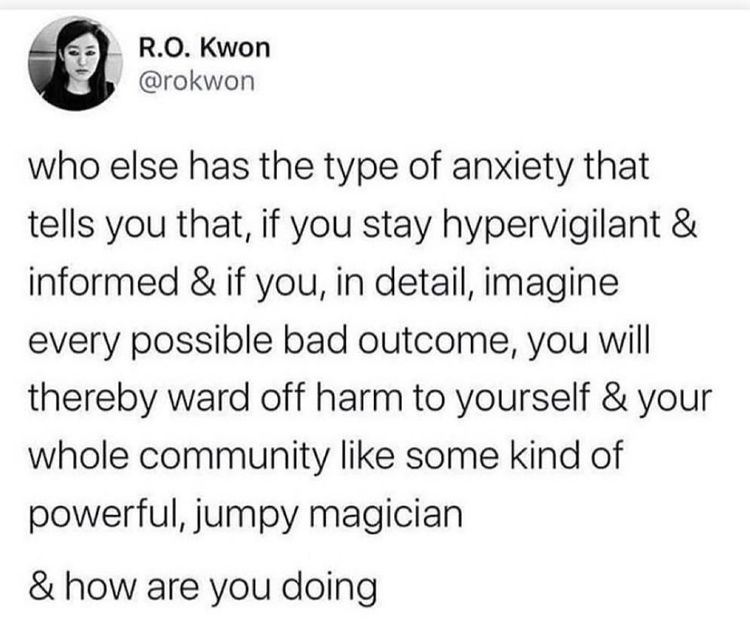

For me, disengagement tends to emerge against a background of a long-standing reliance on external validation and a persistently fragile self-image, factors commonly discussed in research on self-esteem and interpersonal sensitivity (American Psychological Association: Self-esteem). I also have ADHD, and I informally identify with several traits commonly associated with autism spectrum presentations, particularly around social anxiety and interpersonal sensitivity. ADHD is associated with differences in emotional regulation and sensitivity to interpersonal feedback (American Psychological Association: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder).

Social anxiety is frequently discussed in relation to both ADHD and autism spectrum traits (American Psychological Association: Social anxiety disorder). In that context, prolonged relational strain can become especially destabilizing. When I reach a point where being around a person feels actively harmful, and there appears to be no viable way to address or repair that harm, disengagement becomes a form of self-protection rather than a reaction of anger.

At that stage, the person may come to feel emotionally “toxic” to me, not in a moral sense, but in the sense that continued exposure reliably produces distress, a subjective experience consistent with descriptions of emotional stress responses to repeated interpersonal threat or harm (American Psychological Association: Psychological stress). That perceived toxicity often generalizes: it can extend to places, activities, or interests associated with the person, further reinforcing withdrawal.

What This Is Not

This pattern is not a diagnosis, a validated psychological mechanism, or a rule for how people should behave. It is not inherently healthy or unhealthy, and it is not specific to any personality type or framework. It should not be used to excuse avoidance, silence, or a lack of accountability where communication remains possible and appropriate.

Misuse & Failure Modes

A failure mode is a predictable way a system, idea, or process can break down under certain conditions. In the context of the door slam, common failure modes include retroactively justifying impulsive withdrawal, labeling others instead of examining relational or systemic conditions, and treating disengagement as inevitable rather than context-dependent. In organizational settings, similar misattributions are often discussed in analyses of burnout that emphasize workplace structure over individual pathology (Harvard Business Review: Stop Blaming Employees for Burnout). In workplace settings, this pattern is often misapplied to individuals when the underlying causes are structural, cultural, or managerial.

Practical Implications (Work & Teams)

In professional environments, what appears as sudden disengagement is often the final stage of prolonged, unaddressed strain. Reduced communication, emotional detachment, and eventual exit are frequently late-stage responses to chronic stress rather than abrupt decisions, consistent with research on employee withdrawal behaviors (Hulin, Roznowski, & Hachiya, 1985).

Teams that reward endurance over clarity, discourage early boundary-setting, or lack safe escalation paths increase the likelihood of this outcome, a dynamic echoed in contemporary discussions of burnout as a systemic rather than individual failure (Harvard Business Review: Burnout Is About Your Workplace, Not Your People). Conversely, environments that normalize explicit boundaries and respond early to signs of strain reduce the risk of catastrophic disengagement.

Limits and Usefulness

The value of naming late-stage relational disengagement lies in recognizing that withdrawal is often cumulative rather than spontaneous. Understanding this pattern helps explain why some breaks feel sudden yet final, without reducing them to personality flaws or moral failure.

Used carefully, the concept shifts attention from character to conditions. It highlights where strain accumulates, where repair attempts stall, and where boundaries are repeatedly tested or ignored. That understanding does not obligate reconciliation, but it does expand the range of possible responses – earlier intervention, clearer boundaries, or more deliberate disengagement.

This is a lens, not a diagnosis: a way to see a pattern clearly enough to respond to it with intention rather than surprise, and to choose actions that reduce harm rather than merely explain it.

![Today::20230801 [48]](/content/images/size/w750/2023/08/Frame-1.jpeg)

Member discussion